- Elevation & shadows

- Elevation

- Resting elevation

- Dynamic elevation offsets

- Elevation (Android) Expand and collapse content An arrow that points down when collapsed and points up when expanded.

- Resting elevation

- Responsive elevation and dynamic elevation offsets

- Avoiding elevation interference

- Playing with elevation in Android

- What is that shadow all about

- Elevation tweaks in action

- One last thing before you go

- Material Design. Динамический Toolbar на живом примере

- Начнём с постановки задачи

- Создаём xml файлы конфигураций

Elevation & shadows

In the physical world, objects can be stacked or affixed to one another, but cannot pass through each other. Objects also cast shadows and reflect light.

Material Design reflects these qualities to form a spatial model that is familiar to users and can be applied consistently across apps.

Elevation

Measured from the front of one surface to the front of another, an element’s elevation indicates the distance between surfaces and the depth of its shadow.

Resting elevation

All material elements have resting elevations. While components have consistent resting elevations across apps, they may have different resting elevations across platforms and devices.

Dynamic elevation offsets

Dynamic elevation offsets are the goal elevation that a component moves towards, relative to its resting state.

Elevation (Android) Expand and collapse content An arrow that points down when collapsed and points up when expanded.

Elevation is the relative depth, or distance, between two surfaces along the z-axis.

Specifications:

- Elevation is measured in the same units as the x and y axes, typically in density-independent pixels (dp). Because material elements have depth (all material is 1dp thick), elevation is measured in distance from the top of one surface to the top of another.

- A child object’s elevation is relative to the parent object’s elevation.

The images and values shown are for Android apps.

Multiple elevation measurements for two objects

Resting elevation

All material objects, regardless of size, have a resting elevation, or default elevation that does not change. If an object changes elevation, it should return to its resting elevation as soon as possible.

Desktop resting elevation is 2dp below the listed values to accommodate mouse and non-touch environments.

Component elevations:

- Components maintain consistent resting elevations across apps. For example, the floating action button’s elevation does not vary from one app to another.

- Components may have different resting elevations across platforms and devices, depending on the depth of the environment. For instance, TV has a greater depth than desktop as it has a larger screen and is viewed from further away. Similarly, both TV and desktop have a greater depth than mobile.

Responsive elevation and dynamic elevation offsets

Some component types have responsive elevation, meaning they change elevation in response to user input (e.g., normal, focused, and pressed) or system events. These elevation changes are consistently implemented using dynamic elevation offsets.

Dynamic elevation offsets are the goal elevation that a component moves towards, relative to the component’s resting state. They ensure that elevation changes are consistent across actions and component types. For example, all components that lift on press have the same elevation change relative to their resting elevation.

Once the input event is completed or cancelled, the component will return to its resting elevation.

Avoiding elevation interference

Components with responsive elevations may encounter other components as they move between their resting elevations and dynamic elevation offsets. Because material cannot pass through other material, components avoid interfering with one another any number of ways, whether on a per-component basis or using the entire app layout.

On a component level, components can move or be removed before they cause interference. For example, a floating action button (FAB) can disappear or move off-screen before a user picks up a card, or it can move if a snackbar appears.

On the layout level, design your app layout to minimize opportunities for interference. For example, position the FAB to one side of a stream of cards so the FAB won’t interfere when a user tries to pick up one of cards.

Источник

Playing with elevation in Android

Everyone knows that Material Design has shadows. Most know that you can control the virtual Z coordinate of Material elements in Android by using the elevation property, to control the shadow. Very few know that there’s so much more you can do to tweak the shadows your UI elements cast!

Update 6th Nov 2018: I just published a follow-up to this article with new APIs added in P, and a bunch of other goodies. Do check it out!

What is that shadow all about

In Material Design, the elevation is a manifestation of the virtual Z coordinate of a material plane relative to the screen’s “base” plane. For example:

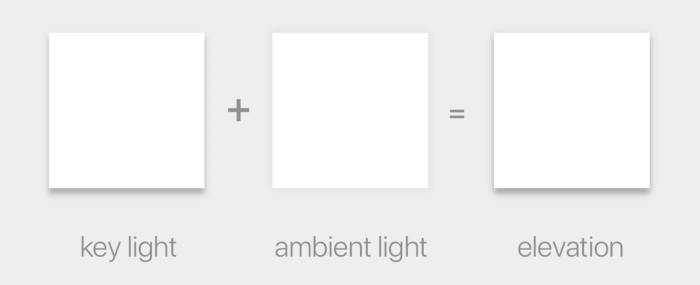

In the Material Design system, there are two light sources. One is a key light that sits above the top of the screen, and an ambient light that sits directly above the centre of the screen:

These two lights cast each their own shadow, one which is mostly affecting the bottom edge of a material sheet (key light), and the other which is affecting all edges (ambient light):

The elevation property directly controls the shape of the resulting shadow; you can see this clearly with buttons, which change their elevation based on their state:

You may think that the elevation property is the only way to control how shadows look, but that’s not true.

In Android, there is a very little known API called Outline that is providing the required information for a Material sheet to project a shadow. The default behaviour for View s is to delegate the outline definition to their background drawable. ShapeDrawable s for example provide outlines that match their shapes, while ColorDrawable s, BitmapDrawable s, etc. provide a rectangle matching their bounds. But nothing says we cannot change that, and tell a view to use a different ViewOutlineProvider , using the setOutlineProvider() method:

If we control the ViewOutlineProvider , we can tweak the resulting Outline , tricking the OS into drawing whatever shadow we want:

You can use elevation and Outline to do all sorts of tweaks to the shape and position of an elevation shadow:

You will notice how the shadow here does not just adapt to different elevation values, but is also translated around and gets a larger or smaller size than the view itself.

Another thing you can do is to assign a shape that is different from the actual outline of the view itself — I cannot think of any situation in which this would make sense, but you could. The only limitation is that the shape must be convex. There are convenience methods on Outline to have ellipses, rectangles and rounded rectangles, but you could also use any arbitrary Path , as long as it’s convex.

Unfortunately it’s not possible to exaggerate some effects too much, since as you can see there are some shortcuts the system takes when rendering the shadows which will create some rather annoying artefacts when you hit them.

In case you are curious how shadows are rendered in Android, the relevant code is in the hwui package in AOSP — you can start looking at AmbientShadow.cpp (note: starting with Android 10, hwui is not really used anymore, and everything is rendered by Skia instead).

Another limitation is that we cannot tint the elevation shadow, we’re stuck with the default grey, but to be honest I don’t believe that’s a bad thing 😉

Elevation tweaks in action

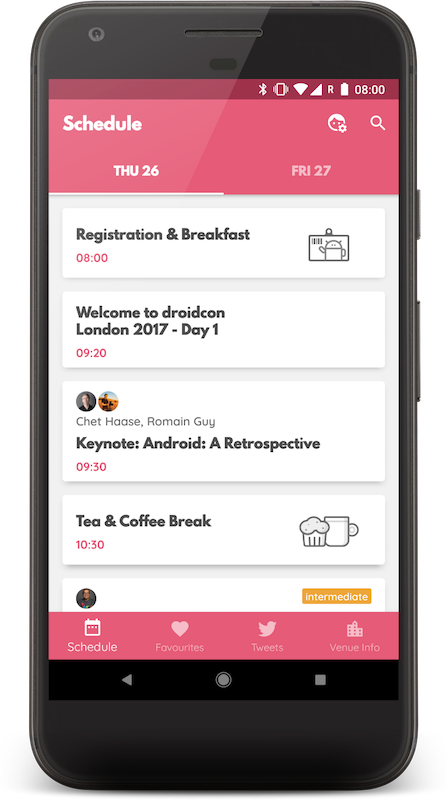

I’ve used this technique to come up with a peculiar elevation appearance for the cards in Squanchy, an open source conference app I’ve been working on in the last year:

As you can see, the cards have a shadow that looks way more diffuse than the regular elevation shadows. This is obtained by having an Outline that is 4dp smaller than the card, and an elevation of 4dp :

The cards have an android:stateListAnimator that also tweaks their elevation and translationZ based on their pressed state, like Material buttons do. You can see how the cardInset* attributes are then used in the CardLayout code to shrink the Outline that we provide to the system.

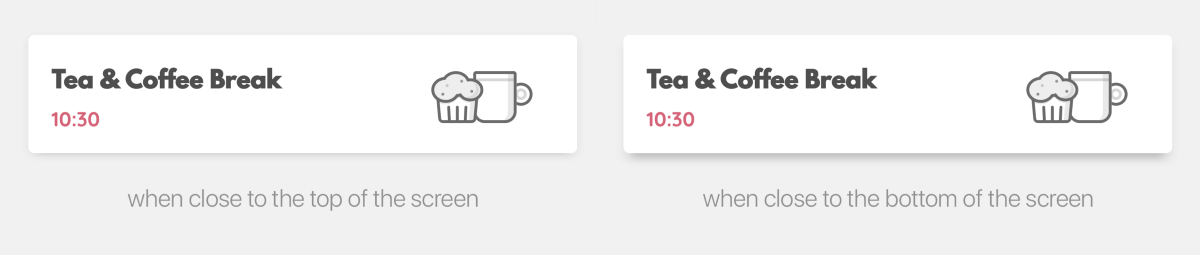

When you scroll the schedule in Squanchy, you might notice that the shadow tends to change size as a card scrolls along the Y axis:

If the effect is too subtle in a gif for you to see, this image makes it crystal clear:

How is that possible? We definitely don’t change the elevation and outline based on the y-position of an item (we could, but it’s really not a good idea as it requires recalculating outlines on each scroll event).

You’ll remember I mentioned earlier how there are two shadows in the Material Design environment, one which sits above the top of the screen, and one that sits directly above the centre. Well, the top light — that is the key light — is casting a longer shadow when an item gets farther away from it. This is actually something that is always true in Android, you just don’t notice it as much in normal circumstances. The Squanchy style makes it more obvious though, and you can even exaggerate it further by using a higher elevation value:

One last thing before you go

Lastly, remember that Outlines aren’t just used for shadows, but by default they define the clipping of the view too! If you have a weird outline and don’t want it to influence the drawing of your actual view, you’ll want to call setClipToOutline(false) on it to avoid nasty surprises.

This is only important when the Outline you provide has canClip() returning true , which is the case when the outline is a rectangle, a rounded rectangle, or a circle. Non-round ovals, and arbitrary paths, are not able to provide clipping, so setClipToOutline() has no effect in those cases.

Fun fact: rectangles and circles are all internally represented as special cases of rounded rectangles. A rectangle is a rounded rectangle with a corner radius of zero, and a circle is a rounded rectangle whose corner radius is equal to half the circle height/width.

If you want to read some more on the topic, the Android Developers website has a page on Defining shadows and clipping views, that goes through the same topics with code examples, and links to some more javadocs.

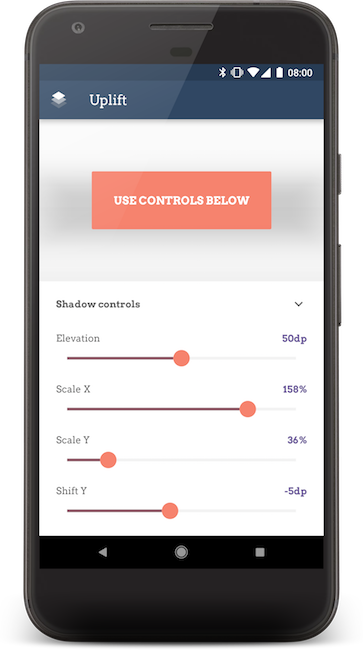

To play around with elevations on your own Android device, I have cooked up a simple playground app:

The code for the playground app is open source on GitHub.

Источник

Material Design. Динамический Toolbar на живом примере

Уверен, что те, кто следят за изменениями в мире Android, заметили, что Toolbar начинает играть в приложениях всё более значимую роль. Например в последней версии Gmail клиента в Toolbar вынесен почти весь функционал по работе с почтой, а в новом Google Chrome Toolbar отвечает за работу с текстом страниц.

В данной статье я постараюсь рассказать о создании динамического Toolbar, который позволит пользователю работать с контентом четырьмя различными способами в рамках одного Activity. Мы рассмотрим весь процесс разработки Toolbar-a начиная с xml файлов стилей и заканчивая анимацией иконок, а в конце статьи я оставлю ссылку на GitHub репозиторий с примером полностью рабочего приложения.

Начнём с постановки задачи

Мы будем разрабатывать Toolbar для приложения, которое позволит пользователю следить за изменениями цен на акции. На главном экране будет расположен список всех акций, за которыми следит пользователь, мы также должны реализовать базовый функционал: удаление, поиск и сортировку акций. Вот так я реализовал этот функционал с помощью динамического Toolbar-a:

| Стандартный режим | Режим поиска | Режим удаления | Режим сортировки |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Создаём xml файлы конфигураций

Итак, в первую очередь нам нужно создать xml файл самого Toolbar-a. Я советую сделать это в отдельном файле, так как в будущем мы скорее всего захотим использовать один и тот же (или похожий) Toolbar во всех Activity нашего приложения.

Теперь мы можем добавить toolbar.xml в xml Activity следующим образом:

res/layout/activity_main.xml

Поскольку в нашем Toolbar будет располагаться виджет поиска, мы можем настроить его внешний в вид в файле styles.xml нашего приложения. В 21 версии Android SDK появилось гораздо больше возможностей для кастомизации виджета поиска (SearchView Widget), вы можете посмотреть полный список атрибутов по этой ссылке: AppCompat v21 — Material Design for Pre-Lollipop Devices! В этом же файле мы зададим цвет нашего Toolbar.

И наконец создадим файл со списком всех элементов нашего Toolbar-а. Тут у нас есть несколько вариантов:

- В начале создать только те элементы, которые будут видны в стандартном режиме, а затем в коде добавлять или удалять элементы при переходе между режимами.

- Сразу создать все существующие элементы в xml файле, а в коде просто управлять их видимостью.

Я выбрал второй вариант так как у нас не так много элементов внутри Toolbar и нам нет смысла экономить память храня в ней только видимые элементы.

Также существует два способа создания элементов Toolbar:

- Создавать элементы внутри меню (Menu), как экземпляры класса MenuItem. Этот способ использовался в предыдущих версиях Анрдроид (API Level

Источник