The Beatles’ rooftop concert (Apple building)

The Beatles began with a rehearsal of ‘Get Back’ while the film cameras were being set up. At the end it was applauded by the spectators on the roof. In response, Paul McCartney mumbled something about cricketer Ted Dexter, and John Lennon announced: “We’ve had a request from Martin Luther.”

Another version of ‘Get Back’ followed. An edit of these two versions was included in the Let It Be film. Afterwards Lennon said: “We’ve had a request for Daisy, Morris and Tommy.”

The third song was ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, as featured in the Let It Be film. Afterwards The Beatles went straight into ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, which was used in both the film and the album. At the end of the song Lennon can be heard saying: “Oh my soul, so hard.”

‘One After 909’ was also used in the Let It Be film and album. At the end of it Lennon broke out into a brief impromptu rendition of Conway Twitty’s 1959 hit ‘Danny Boy’.

The sixth song The Beatles played was ‘Dig A Pony’. A short rehearsal was played first, with Lennon asking for the lyrics. They then performed the song properly, with a production runner on the film, Kevin Harrington, kneeling in front of Lennon holding a clipboard bearing the lyrics. George Harrison, too, briefly knelt next to Harrington.

‘Dig A Pony’ began with a false start. In the film, Ringo Starr can be seen putting his cigarette down and crying out ‘Hold it!’ This, and the full version that followed, were both included in the album and film, although on the LP the ‘All I want is…” refrain which opened and closed the song were later cut by Phil Spector.

George Harrison joined Lennon and McCartney on vocals for the excised lines from ‘Dig A Pony’. He also contributed minor backing vocals to ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’.

As Alan Parsons changed the recording tapes in Apple’s basement studio, The Beatles and Billy Preston performed an off-the-cuff version of ‘God Save The Queen’. This was never used; nor were second versions of ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’ and ‘Don’t Let Me Down’.

The final full song was ‘Get Back’, although The Beatles nearly stopped performing when the police arrived on the roof. The officers demanded that Mal Evans turn off the group’s Fender Twin amplifiers. He complied, but Harrison immediately turned his back on.

Evans realised his mistake and turned Lennon’s back on too. The amplifiers took several seconds to start again, but The Beatles managed to continue long enough to see the song through to the end.

We kept going to the bitter end and, as I say, it was quite enjoyable. I had my little Hofner bass – very light, very enjoyable to play. In the end the policeman, Number 503 of the Greater Westminster Council, made his way round the back: ‘You have to stop!’ We said, ‘Make him pull us off. This is a demo, man!’

I think they pulled the plug, and that was the end of the film.

As a climax it could scarcely be bettered, with McCartney brilliantly ad-libbing, “You’ve been playing on the roofs again, and that’s no good, and you know your Mummy doesn’t like that… she gets angry… she’s gonna have you arrested! Get back!”

The police presence ensured that The Beatles would play no more on the roof. The concert over, McCartney thanked Starr’s wife Maureen for her enthusiastic cheering with a simple “Thanks Mo”.

Then, of course, there was John Lennon’s immortal closing quote: “I’d like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves, and I hope we’ve passed the audition.” Both these comments were used at the end of ‘Get Back’ on the Let It Be album, although the version of the song was not from the rooftop performance.

Around half of the performance was used in the Let It Be film. Furthermore, edits of ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, ‘One After 909’ and ‘Dig A Pony’ all featured on the Let It Be album.

The final ‘Get Back’ take was included in the Let It Be film, and appeared on Anthology 3 in 1996.

An edit of the two ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ takes was included on 2003’s Let It Be… Naked, due to John Lennon getting the vocals wrong at different points in both. That album also contained an edit of the rooftop performance of ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’ and another version, recorded on another date.

Источник

The Beatles’ rooftop concert (Apple building)

Apple Studios, Savile Row, London

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Glyn Johns

The Beatles, with Billy Preston, gave their final live performance atop the Apple building at 3 Savile Row, London, in what became the climax of their Let It Be film.

We set up a camera in the Apple reception area, behind a window so nobody could see it, and we filmed people coming in. The police and everybody came in saying, ‘You can’t do that! You’ve got to stop.’

30 January 1969 in London was a cold day, and a bitter wind was blowing on the rooftop by midday. To cope with the weather, John Lennon borrowed Yoko Ono’s fur coat, and Ringo Starr wore his wife Maureen Starkey’s red mac.

The 42-minute show was recorded onto two eight-track machines in the basement of Apple, by George Martin, engineer Glyn Johns and tape operator Alan Parsons. The tracks were filled with the following: Paul McCartney, vocals; John Lennon’s and George Harrison’s vocals; Billy Preston’s organ; McCartney’s bass guitar; a sync track for the film crew; Starr’s drums; Lennon’s guitar; Harrison’s guitar.

The songs performed on the roof:

Brief, incomplete and off-the-cuff versions of ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, ‘God Save The Queen’, and ‘A Pretty Girl Is Like A Melody’ were fooled around with in between takes – as was ‘Danny Boy’, which was included in the film and on the album. None of these were serious group efforts, and one – the group and Preston performing ‘God Save The Queen’ – was incomplete as it coincided with Alan Parsons changing audio tapes.

The Beatles’ rooftop show began at around midday. The timing coincided with the lunch hour of many nearby workplaces, which led to crowds quickly forming. Although few people could see them, crowds gathered in the streets below to hear The Beatles play.

Traffic in Savile Row and neighbouring streets came to a halt, until police from the nearby West End Central police station, further up Savile Row, entered Apple and ordered the group to stop playing.

We decided to go through all the stuff we’d been rehearsing and record it. If we got a good take on it then that would be the recording; if not, we’d use one of the earlier takes that we’d done downstairs in the basement. It was really good fun because it was outdoors, which was unusual for us. We hadn’t played outdoors for a long time.

It was a very strange location because there was no audience except for Vicki Wickham and a few others. So we were playing virtually to nothing – to the sky, which was quite nice. They filmed downstairs in the street – and there were a lot of city gents looking up: ‘What’s that noise?’

Источник

The Beatles’ Rooftop Concert: Behind The Group’s Final Public Performance

In their final public performance, The Beatles made history playing on top of the Apple Studios, becoming the most famous rooftop concert of all time.

January 30, 2021

Recorded as the B-side of “Get Back” on January 28, 1969, “Don’t Let Me Down” was first heard outside of the recording studio two days later, on January 30, when The Beatles played it a rooftop concert at Apple Studio in Savile Row, London. Written by John Lennon as an expression of his love for Yoko Ono, the song is heartfelt and passionate. As John told Rolling Stone magazine in 1970, “When it gets down to it, when you’re drowning, you don’t say, ‘I would be incredibly pleased if someone would have the foresight to notice me drowning and come and help me,’ you just scream.”

Joining The Beatles at Apple Studios for both sides of the single was keyboard player Billy Preston, who gives the track such a beautiful, gentle feel, contrasting brilliantly with the intensity of John’s lead vocal. Billy was credited on the Apple single and it charted in America, but airplay of “Get Back” predominated and propelled the A-side to No.1 on the charts for five weeks. By comparison, “Don’t Let Me Down” got much less exposure. It’s another of those B-side gems that, with the passing of time, people have come to appreciate more.

During filming of the rooftop concert, The Beatles played “Don’t Let Me Down” right after doing two versions of “Get Back,” and it led straight into “I’ve Got A Feeling.” Michael Lindsay-Hogg directed The Beatles’ shoot, and both he and Paul McCartney met regularly at the tail end of 1968, while Hogg was directing The Rolling Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus, to discuss the filming of The Beatles’ session in January. By the time that fateful Thursday came around, the penultimate day of January would be the last time The Beatles ever played together in front of any kind of audience.

On this video, it’s not the version of “Don’t Let Me Down” heard on the single but the version from the Let It Be… Naked album – a composite of both versions that were performed on the most famous rooftop concert of all time.

The Beatles rooftop concert featuring “Don’t Let Me Down” can be found on the Beatles’ 1s DVD/Blu-ray, which can be bought here.

Follow the This Is The Beatles playlist for more essential Beatles.

Источник

Beatles on the brink: how Peter Jackson pieced together the Fab Four’s last days

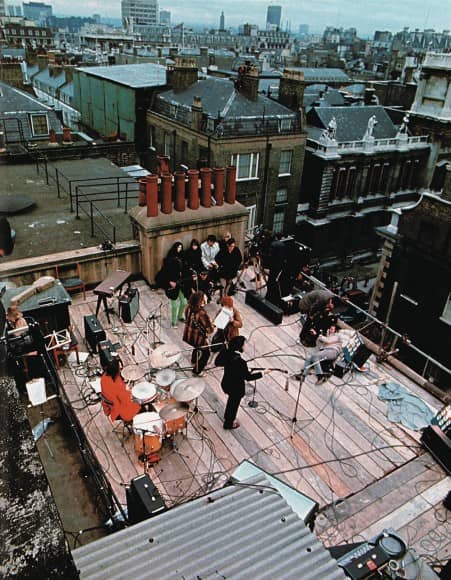

The Beatles perform on the roof of the Apple Corps building, 3 Savile Row, London W1, 30 January 1969 – the final public performance of their career. Photograph: Ethan A Russell/© Apple Corps Ltd

The Beatles perform on the roof of the Apple Corps building, 3 Savile Row, London W1, 30 January 1969 – the final public performance of their career. Photograph: Ethan A Russell/© Apple Corps Ltd

The director’s new documentary weaves together hours of unseen footage to dispel many myths about the band’s final months. John Harris, who was involved in the project, tells the inside story

Last modified on Sun 26 Sep 2021 09.51 BST

O n paper, the idea looked brilliant. In the opening weeks of January 1969, the Beatles were working up new songs for a televised concert, and being filmed as they did so. Where the event would take place was unclear – but as rehearsals at Twickenham film studios went on, one of their associates came up with the idea of travelling to Libya, where they would perform in the remains of a famous amphitheatre, part of an ancient Roman city called Sabratha. As the plan was discussed amid set designs and maps one Wednesday afternoon, a new element was added: why not invite a few hundred fans to join them on a specially chartered ocean liner?

Over the previous few days, John Lennon had been quiet and withdrawn, but now he seemed to be brimming with enthusiasm. The ship, he said, could be the setting for final dress rehearsals. He envisaged the group timing their set so they fell into a carefully picked musical moment just as the sun came up over the Mediterranean. If the four of them had been wondering how to present their performance, here was the most gloriously simple of answers: “God’s the gimmick,” he enthused.

Paul McCartney seemed just as keen: “It does make it like an adventure, doesn’t it?” he said. Ringo Starr said he would rather do the show in the UK, but did not rule out the trip: “I’m not saying I’m not going,” he offered, which sounded as if he was open to persuasion.

But George Harrison was not interested. He feared “being stuck with a bloody big boatload of people for two weeks”. The idea of getting to Libya on a ship, he insisted, “was very expensive and insane”. When Lennon suggested they could get a cruise liner for free from P&O, Harrison flatly pointed out that, despite their celebrity, the Beatles had trouble even getting complimentary guitar amps.

Among an array of other ideas for a concert venue, there were also mentions of the Royal Albert Hall, the Tate Gallery, an airport, an orphanage and the Houses of Parliament. But whatever the suggested setting was, everything seemed to founder on a mixture of inertia, logistical impossibility and Harrison’s implacable opposition. Indeed, two days after the longest conversation about Sabratha, Harrison would temporarily walk out of rehearsals, with the deadpan line: “See you round the clubs.” When he returned, it was seemingly on the basis that the idea of a spectacular live performance would be shelved.

In the end, there was a compromise. Having begun working at Twickenham, the Beatles relocated to a makeshift studio in the basement of 3 Savile Row, the central London address that was the home of their company Apple. The plan for a televised concert was abandoned, and it was agreed – just about – that the group were now being filmed for a feature-length documentary. And on Thursday 30 January, the four of them – joined by the American keyboard player and singer Billy Preston – played, with a mixture of panache and joyous energy, on the Apple building’s roof. No one knew it was their last public performance, but, in retrospect, they ensured that such a significant moment passed off almost perfectly.

‘Contrary to myth, they were still closely collaborating’: the Beatles and Yoko Ono at Apple Studios, 24 January 1969. Photograph: Ethan A Russell/© Apple Corps Ltd

Such was the finale of four weeks of filming and recording that eventually resulted in an 80-minute feature-length film titled Let It Be, and the album of the same name. What remained in the Beatles’ vaults – although some of it subsequently fell into the hands of bootleggers – was 50 additional hours of rushes and more than twice as much audio, brimming with an immersive sense of who they were and how they worked.

Eventually, in preparation for Let It Be’s 50th anniversary, most of this material was collected together. In 2017, Apple recruited the New Zealand-based director Peter Jackson – the creator of the six film versions of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, as well as the documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, built from restored footage of the first world war – to cut a new feature-length film. As it eventually turned out, the pandemic made a normal theatrical release impossible, and opened up the possibility of something even more ambitious. Jackson ended up creating three two-hour documentaries, which will premiere at the end of November on the streaming platform Disney+.

As Jackson puts it, his new films tell the story of the Beatles “planning for a concert that never takes place”, and “a concert that does take place, which wasn’t planned”. Thanks to his and his team’s restoration work, everything is pin-sharp, and unbelievably evocative of time and place: the tale unfolds in a London of trilby hats, Austin Powers-esque fashions and copious cigarette smoke. But the films’ key attribute is their intimacy, and the light they shine on the Beatles’ instinctive creativity, their deep personal bonds and, as they neared their final split, their thoughts about their future.

What remained in the Beatles’ vaults was 50 additional hours of rushes and more than twice as much audio

The three-part documentary series is titled Get Back, and forms the central part of a huge new project that also includes an expansive package of music and a book. The latter features photographs by Linda McCartney and Let It Be’s on-set photographer Ethan Russell, and detailed transcripts of the Beatles’ often candid conversations – which, it still amazes me to say, I was given the job of editing down from raw material made up of hundreds of thousands of words, and about 120 hours of audio.

For someone who has been a passionate Beatles fan since the age of about eight, it was a dream job (circa 1981, Let It Be was the first Beatles album I ever bought, on a family holiday in Yorkshire). When I recently spoke to Jackson, something he said got to the heart of what an amazing project this was: “To have intimate, behind the scenes, fly on the wall coverage of the recording of an album from a band in the 60s is one thing. But the fact that it’s the Beatles is mind blowing, really.”

I n September 1968, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, a one-time director of the trailblazing TV pop show Ready Steady Go!, gathered the Beatles at Twickenham to film the promotional video for Hey Jude, in front of a small crowd that joined them for the song’s “na-na-na” ending. Between takes, they spontaneously played rock’n’roll standards, and were reminded of the pleasures of performing for an audience. By late autumn, in the wake of the completion of the so-called White Album, this realisation had flowered into a plan – for the Beatles’ first proper concert since August 1966, which would largely be made up of completely new songs. Lindsay-Hogg and his crew would film rehearsals for an appetite-whetting half-hour TV film, before the cameras captured the Beatles’ climactic performance at an undecided location, which would then be broadcast around the world.

What then happened, as the concert idea shrank and the group took the default option of making another album, has been routinely portrayed as an all-time low. Read the accounts of this period in any number of Beatles books and you will find words such as “crisis”, “nadir” and “impasse” in abundance. During the time when his interviews were often full of seething resentment, Lennon – who was accompanied throughout the sessions by Yoko Ono – added a quotation to Beatles lore that has long stuck to this period: “Even the biggest Beatle fan couldn’t have sat through those six weeks of misery. It was the most miserable session on earth.” McCartney, whose take on this period was always a bit more measured, said that Let It Be “showed how the breakup of a group works”.

When fame reaches a certain point, facts blur into mythology and received opinion. And in Let It Be’s case, the film’s reputation as a story of endless misery and strife was partly due to its timing. The original movie was released over a year after it was filmed, in May 1970, only a month after McCartney had confirmed that the Beatles had broken up, and was therefore received as a portrait of a group in its death throes. As the ensuing years went by, in the absence of an official rerelease on DVD, the fact that most Beatles fans only saw murky third and fourth-generation versions hardly helped.

The cover of the Beatles’ final album together, released in May 1970. Photograph: © Apple Corps Ltd

What the new documentary series, book and audio reveal is something much more nuanced and complicated. In hindsight, the Beatles were indeed moving towards their end. Many of the tensions that fed into their split are clearer: their divisions over returning to live performance, Harrison’s growing confidence and the dissatisfaction that came with it, the unease and bafflement sown by Ono’s arrival right at the group’s core. But the business tensions that would decisively divide them had yet to explode – and early ’69 saw them still creating wondrous music, and largely getting on very well.

This is the central revelation of the Get Back project. After Jackson had begun work on the rushes, I was approached by Apple executive Jonathan Clyde about writing an accompanying book. He told me about the long hours of on-set conversation and creativity that had been captured on two constantly whirring tape recorders, even when the cameras were not rolling. Some of this stuff had been reproduced in a book that came with initial pressings of the Let It Be album put together by the American producer Phil Spector back in 1970; now, the idea was to come up with something altogether more exhaustive and definitive.

Over the next weeks and months, I took delivery of 21 spiral-bound books of meticulous transcripts, and was given access to all the audio recordings. I was also loaned an iPad by Apple, which contained just about all the restored rushes: a magic-box of revelations that filled in many gaps, allowing me to understand the nuances of dialogue via facial expressions and watch scenes that had no accompanying audio. Editing down such a mountain of raw material into a 50,000-word text – around half of which reproduces material that isn’t in the new films – was a lengthy process, but every day delivered surprises and pleasures.

A lot of these centred on how the Beatles made music. Contrary to myth, they were still closely collaborating, a point illustrated by a sequence in which Harrison asks the others for help on a love song he has been working on for months, soon to be titled Something. He was stuck on this new song’s second line:

Harrison: “What could it be, Paul? It’s like, I think of what attracted me at all.”

Lennon: “Just say whatever comes into your head each time: ‘Attracts me like a cauliflower’… until you get the word, you know.”

Harrison: “Yeah, but I’ve been through this one for about six months.”

Lennon: “You haven’t had 15 people joining in, though.”

Harrison: “No. I mean just that line. I couldn’t think of anything like a…”

John: [sings] “‘Something in the way she moves / Attracts…’ ‘Grabs’ instead of ‘attracts’.”

George: “But it’s not as easy to say…”

Lennon: “Grabs me like a southern honky-tonk…”

In between the music came endless conversations – about their history, what they would have for lunch, their hangovers

Harrison and Lennon: [singing] “Something in the way she moves / And like a la-la-la-la-la…”

Lennon: “Grabs me like a monkey on a tree…”

Lennon and Harrison: [singing] “Something in the way she moves / And all I have to do is think of her / Something in the way she shows…”

Harrison: [sings] “‘Attracts me like a pomegranate…’ We could have that: ‘Attracts me like a pomegranate.’” [laughs]

Lennon and Harrison: [singing] “Something in the way she moves / Attracts me like a moth to granite…”

The day before, Harrison had arrived at Apple dressed in a dazzling white and purple suit, sat at the piano, and premiered another new song. If you want an instant antidote to the idea that the Let It Be sessions were thoroughly miserable and rancorous, what followed is perfect:

McCartney: “How are you?”

Harrison: “Oh, I went to bed very late. I wrote a great song actually… [enthusiastically] happy and a rocker.”

Lennon: “It’s such a high when you get home… I’m just so high when I get in at night.”

Harrison: “Yeah, it’s great isn’t it?”

Lennon: “I was just sitting there listening to the last takes: ‘What have I had? What have I had today?’ You know, I ask her [Ono], ‘Have we had anything?’”

Ono: “You’re just high in general.”

Lennon: “Just want to… Wooooaah! I just can’t sleep…”

Harrison: “I keep thinking, ‘Oh, I’ll just go to bed now’, and then I keep hearing your voice from about 10 years ago, saying, ‘Finish [the song] straight away: as soon as you start ’em, you finish ’em.’ You once told me…”

Lennon: “Oh, the song… But I never do it, though. I can’t do it. But I know it’s the best.”

McCartney [to Harrison]: “Well, what’s it called?”

George: “I’ve no title. Maybe you can see a title in it somewhere.”

He then played Old Brown Shoe, which would appear on the B-side of The Ballad of John and Yoko. McCartney gamely joined in on drums, and then a guitar he played upside down; Billy Preston played bass. Later the same day, the five of them recorded a superb version of Get Back – the rollercoaster piece of rock’n’roll that was arguably this period’s defining song.

“This is so good – this is great,” enthused Glyn Johns, the recording engineer and producer who was in charge of getting everything on tape. When George Martin, their usual producer, paid the sessions one of many visits, he was even happier: “You’re working so well together: you’re looking at each other, you’re seeing each other, you’re just happening.” Music was pouring out of them: not just the best songs that would be performed in the Let It Be film (the title track, Get Back, The Long and Winding Road, Two of Us, Don’t Let Me Down), but a big chunk of Abbey Road, and other creations destined for their solo albums.

In between the music came endless conversations – about their distant history in Liverpool and Hamburg, what they would have for lunch (one Harrison favourite was “big, fresh, uncut mushrooms”), and their hangovers (Starr: “I won’t lie – I’m not too good”). They habitually discussed what had been on TV the previous night, from Peter Cook clashing with Zsa Zsa Gabor to BBC Two’s science fiction, and talked about politics, as evidenced by a sendup of the demagogic politician Enoch Powell and a heartfelt conversation about Martin Luther King. There were also hundreds of mentions of other musicians: Fleetwood Mac, Frank Sinatra, Bob Dylan and the Band, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin.

T he Beatles also talked about something much more dramatic: the prospect of their own split, and the tensions that sometimes flared up as the cameras rolled. A lot of these ruminations happened just after Harrison’s walkout, crisply recorded in his diary: “Got up, went to Twickenham, rehearsed until lunchtime, left the Beatles.” In his absence, Starr, McCartney and Lennon (who said that if Harrison didn’t return, they could recruit Eric Clapton) still turned up at Twickenham film studios. Even if the group’s sensitivities meant that he couldn’t use the resulting material in Let It Be, Lindsay-Hogg had the presence of mind to gently encourage them to talk about their internal relationships, and where the group might be going.

He also surreptitiously hid a microphone near the table in the studio canteen where Lennon, Ono and McCartney had lunch, and recorded a remarkable conversation. On the audio I was given, it began suddenly and unexpectedly:

Lennon: “I mean, I’m not going to lie, you know. I would sacrifice you all for her [Ono]… She comes everywhere, you know.”

McCartney: “So where’s George?”

Lennon: “Fuck knows where George is.”

Ono: “Oh, you can get back George so easily, you know that.”

Lennon: “But it’s not that easy because it’s a festering wound… and yesterday we allowed it to go even deeper, and we didn’t give him any bandages.”

McCartney: “See, I’m just assuming he’s coming back, you know. I’m assuming he’s coming back.”

Lennon: “Well, do you…”

McCartney: “If he isn’t, then he isn’t; then it’s a new problem.”

Lennon: “If we want him – I’m still not sure whether I do want him – but if we do decide we want him as a policy, I can go along with that because the policy has kept us together.”

When Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ manager, had died suddenly in the summer of 1967, it was McCartney who had quickly taken on the role of coming up with new ideas and instigating work in the studio. Thanks partly to Lennon’s resulting resentments, the received view of Beatles history has tended to frame this aspect of the group’s relationships in terms of McCartney’s supposed bossiness, but what the films and book tend to show are very different qualities: empathy, sensitivity and the patience needed to get four increasingly different people to move in roughly the same direction.

When there was a discussion about Ono’s permanent new place at Lennon’s side, McCartney cautioned against trying to get in the way. “They’re going overboard about it, but John always does, you know, and Yoko probably always does. So that’s their scene. You can’t go saying: ‘Don’t go overboard about this thing, be sensible about it and don’t bring her to meetings.’ It’s his decision, that. It’s none of our business starting to interfere in that.” He also had a prescient sense of how future historians would understand the Beatles’ breakup: “It’s going to be such an incredible sort of comical thing, like, in 50 years’ time: ‘They broke up cos Yoko sat on an amp’… or just something like that. What? ‘Well, you see, John kept bringing this girl along.’ What? It’s not as though there’s any sort of earth-splitting rows or anything.”

McCartney could also be assertive and blunt, something that happened early in the rehearsals, at Twickenham, when the prospect of a big live show was starting to recede.

The band, joined by keyboardist Billy Preston (bottom right), on the roof of the Apple Corps building, 1969. Photograph: Ethan A Russell/©Apple Corps Ltd

“As far as I can see it, there’s only two ways – and that’s what I was shouting about in the last meeting we had,” he said. “We’re going to do it, or we’re not going to do it. And I want a decision. Because I’m not interested enough to spend my fucking days farting round here while everyone makes up their minds whether they want to do it or not, you know. I’ll do it. If everyone else will, and everyone wants to do it, then all right. But [laughs], you know, it’s just a bit soft. It’s like at school, you know. ‘You’ve got to be here!’ And I haven’t! You know, I’ve left school. We’ve all left school…”

Though their split was initially hushed up, the Beatles would soon be no more. But in the meantime, they managed to surmount their differences. They didn’t make it to Sabratha, or the Royal Albert Hall, or the Tate Gallery, but when they played on top of the Apple offices, the music and the spectacle they created made it a triumph. Glances passed between them, seemingly in recognition of how great it all felt and sounded – and amid the mayhem on the street below, when two Metropolitan police officers tried to shut everything down, the episode was injected with a lovely rebellious romance. “They rocked and rolled and connected as they had in years gone by, friends again,” Lindsay-Hogg later wrote. “It was beautiful to see.”

Half a century later, we now know that was not some fluke, but the end result of four weeks that, after a very shaky start, had gone much better than all those subsequent accounts suggested – something crystallised in a couplet Lennon added to McCartney’s song I’ve Got a Feeling, which they played twice on the roof. “Everybody had a hard year,” he sang, into the January chill. “Everybody had a good time.”

The Get Back book is published by Apple and Callaway on 12 October. The new expanded and remixed versions of Let It Be are available from 15 October. The three-part Get Back documentary series is on Disney+ from 25-27 November

Источник