- Big apple new york circus

- Big Apple Circus

- From Circopedia

- Contents

- New York’s One-Ring Wonder

- It All Started in San Francisco

- From The Streets of Europe to The Nouveau Cirque de Paris

- The Project

- Raising The Tent

- «The Circus of Picture-Books and Tribal Memory»

- «The Only Circus Good Enough to Play Lincoln Center»

- The End of An Era

- Epilogue?

Big apple new york circus

Returns to Lincoln Center Nov. 11

Tickets go on sale September 26 at noon

New York, NY — For the first time in the Wallenda family’s 200 year history, world-renowned aerialist, high wire artist and Guinness World Record holder, Nik Wallenda will helm the production of The Big Apple Circus , a circus he has chosen to revive.

Aptly titled “Making The Impossible, Possible!” Wallenda has partnered with a team of live entertainment super producers from the circus world, live music and Broadway — Phillip Wm. McKinley , Michael Cohl and Arny Granat — to make Big Apple Circus even better, and more exciting by adding a modern flair to this beloved classic.

Revered for its intimate and artistic style, the producers are passionate about revitalizing the circus for modern-day audiences, with unique and astounding human feats from performers with incredible real-life stories.

A New York Times Critic’s Pick every year since its reconstitution in 2017, Big Apple Circus continues a long-standing tradition of inclusivity, highlighting the finest talent from around the globe for an equally diverse audience

The Big Apple Circus will return to Lincoln Center on Nov. 11

Tickets go on sale Sunday September 26th at noon at www.bigapplecircus.com

Wallenda, a world-renowned aerialist who has been featured in five nationally televised TV specials is the first and only person in the world to walk a wire directly over Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon and an active volcano.

Seen by over 250,000 people in Times Square, Nik, will be joined by his family of thrilling high wire artists, and an all-new award winning cast from Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Ethiopia, Germany, Russia, and the United States, some of whom have previously been featured on America’s Got Talent, YouTube and The X-Factor.

For decades, The Big Apple Circus captured the hearts of New Yorkers with death-defying feats that produce oohs, ahhs and gasps throughout the crowd, putting a contemporary twist on the beloved classic. The show was forced to close in 2017 due to financial challenges and after reopening had to shut down again due to the pandemic. However, the revival has been several months the making, with Wallenda, McKinley, Cohl and Granat bringing their extensive credentials to the table:

- Director Philip Wm. McKinley has directed record-breaking productions from Broadway to Salzburg to Tokyo. Known for his direction of spectacle, his work includes the blockbuster Spiderman: Turn off the Dark, the Tony nominated The Boy from Oz and the water spectacular Le Reve at the Wynn Hotel Las Vegas.

- Emmy and Tony Award winner Michael Cohl is CEO of S2BN Entertainment and the former Chairman of Live Nation. Over his career he has produced and promoted tours for some of the biggest musical and theatrical acts in the world including Moscow Circus Bolshoi, Spiderman turn off the Dark, Bat Out of Hell, the Musical, Rock of Ages, Yo Gabba Gabba, Barbra Streisand, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, and U2.

- Arny Granat is CEO of Grand Slam Productions and co-founded Jam Productions, which became one of the largest independent concert promoters in North America. He has won nine Tony Awards for shows including “Spamalot,” and “The Band’s Visit!”and promoted the first ever Farm Aid concert and has worked on tours for Robin Williams, Rolling Stones, Madonna, Eric Idle. Frank Sinatra and the Baseball Hall of Fame traveling exhibit.

“Circus entertainment is family entertainment, and we want to invite your family to be a part of ours. We can’t wait to reveal the new show that will certainly mix traditional circus with modern updates,” said Wallenda.

“Working with these three legendary producers who are so passionate about revitalizing the Big Apple Circus, we have come up with a jaw-dropping show that will captivate our audience,” McKinley said.

“We were in disbelief when the doors of the Big Apple Circus shuttered, but now it’s time for one of America’s most endearing shows to make a triumphant return. We plan to offer new surprises in a safe, family environment and hope it will provide some respite from this rough period in our country. We’re looking forward to welcoming back the kids, and presenting an amazing evening for parents and their kids that’s safe for everyone , but Nik’, said Cohl.

“I’m proud to partner with Michael, Nik and Phil to present the Big Apple Circus to fans who have been missing out on this one-of-a-kind entertainment. We’re determined to make it an experience you won’t forget,” added Granat.

The Big Apple Circus will follow New York State, New York City and CDC guidelines to ensure the safety of our Big Apple Circus guests, cast, employees and production staff, as a priority. Attendees over 12 must wear masks inside and show proof of vaccination. Children under 12 must wear masks.

Источник

Big Apple Circus

From Circopedia

Contents

New York’s One-Ring Wonder

By Dominique Jando

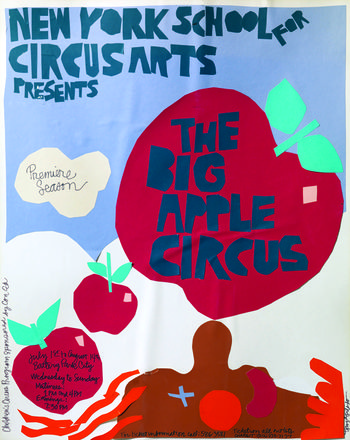

A cherished New York Institution, the original, not-for-profit Big Apple Circus was created in 1977 by Paul Binder and his juggling partner, Michael Christensen, as the performing arm of the New York School for Circus Arts. Its enormous success soon put the school in the shadows, and the circus took over as the principal activity of the organization. It became one of the world’s most respected and successful circuses—until the economic crisis of 2008, which dramatically impacted its fund-raising capacity, sadly led it to file for bankruptcy eight years later.

Its name and equipment were sold to private investors who brought the Big Apple Circus back to life in September 2017 in its traditional winter venue, Damrosch Park, in New York’s prestigious Lincoln Center for The Performing Arts. The new Big Apple Circus quickly abandoned its spring-summer tours of the northeast United States and beyond, and limited its activity to its Lincoln Center four-month winter season. However, the Covid pandemic prevented it from performing in the winter of 2020-21. (As of June 2021, it is not yet known if it will resume its performances.)

It All Started in San Francisco

Later, Paul attended Dartmouth College, where he joined the Dartmouth Players and the Hopkins Center Repertory Theatre, and then earned an MBA at Columbia University. After a brief stint at Boston University’s School of Fine and Applied Arts, he went to work on television as stage manager for Julia Child’s cooking shows, and later as talent coordinator for The Merv Griffin Show. It was the end of the 1960s, and Paul was restless with the times.

Meanwhile, in Walla-Walla, Washington, where he was born, Michael Christensen was struggling with a difficult childhood. Somehow, he needed to act out the feelings stirred by his uneasy life, so, quite naturally, he enrolled in the Professional Actor Training program at the University of Washington. As for the circus: «When the circus came to town in the summer, I helped setting up the tents with my brother in exchange for free passes. I also remember laughing uncontrollably at a clown gag—but I don’t remember who the clown was nor what was the gag.»

Both Paul and Michael ended up in San Francisco, where they met at the San Francisco Mime Troupe. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, San Francisco was the epicenter of a whole era of student revolt and social change. The San Francisco Mime Troupe was taking in active part in that change through a political street-theater movement aimed at stimulating people through outrageous, right-in-your-face physicality.

One of the techniques used by the Mime Troupe to convey their messages was juggling. Michael and Paul learned juggling, and notably «passing,» with co-member Larry Pisoni, with whom Michael developed a juggling comedy routine. Pisoni would go on to become the founder of San Francisco’s fabled Pickle Family Circus, and a great American clown Generic term for all clowns and augustes. »’Specific:»’ In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team. .

Then Larry and Michael decided to go and see the world. They would do their «grand tour,» as the wealthy European youth of centuries past had done, and survive by juggling on street corners, as the wealthy European youth had certainly never done. Michael flew to London first, but soon after, Larry let him know that couldn’t join him. It was a letdown, but Michael didn’t want to return home empty-handed. Luckily, Paul heard of the situation and called Michael to offer himself as a replacement.

Paul and Michael had been occasional juggling partners, and Paul was familiar with Larry and Michael’s routine. Michael was relieved indeed, and Paul flew to London. Thus began what was to become part of the Big Apple Circus’s lore and legend—Paul and Michael’s epic juggling journey through the big cities and one-horse towns of Europe.

From The Streets of Europe to The Nouveau Cirque de Paris

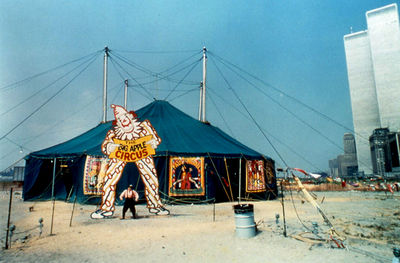

It was a journey of many encounters and discoveries, some of which would be prophetic. In Paris, they met and befriended a fellow street performer (there were only a few of them at the time) named Philippe Petit. Later, in 1974, Philippe managed to string a cable between the tops of the not-yet-completed twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York and became instantly famous.

They went as far as Istanbul and the Bosporus. On the other side of the strait lay Asia, the Orient, the Unknown. «I burst into tears,» Paul recalled, «I was sure that on the other side of that water was madness. We were crazy enough already.» They decided it was time to reverse their path, so they juggled their way back to Paris.

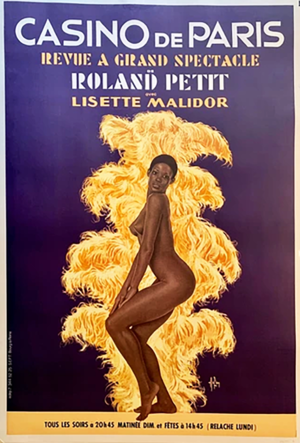

Michael and Paul were performing their act on the Boulevard Saint-Germain when a man who worked as a theater usher approached them. Would they be interested in auditioning for Roland Petit? The famous choreographer had produced a very successful revue for the legendary Casino de Paris, Zizi je t’aime!, which had starred his wife, Zizi Jeanmaire. By then, Jeanmaire had been replaced by Lisette Malidor, and Petit, who was revamping the production, needed fresh talent.

Why not? In front of Roland Petit, the duo performed their act honed on the streets of Europe: Comic juggling involving a rubber chicken named Leonard, with all dialogue performed in American-accented French. It was pure novelty, and it was funny. Thus Paul and Michael appeared at the Casino de Paris, which led them to be booked onto French television. France had only three television channels then, and to be booked on any of them meant big exposure. And by chance, Annie Fratellini and Pierre Étaix happened to be watching the show.

Annie Fratellini had left the circus for a relatively successful singing and acting career. Pierre Étaix starred her in his aptly titled film Le Grand Amour (1969) and convinced her to return to her circus roots. Together, they created what was to become a legendary clown duet. They were also in the process of developing a professional circus school and a circus to go with it. They asked Paul and Michael if they would like to participate in a show they were putting together? Would they like to be part of the first tour of their Nouveau Cirque de Paris? «Yes, why not?» was the answer to these questions.

This chance encounter turned into an epiphany. «Everything led to and came from this experience,» said Paul. Added Michael: «What I believe led Paul to vocalize the idea for the Big Apple Circus was the joy that we felt doing this job. There was a tremendous amount of joy that we felt with each other as we worked in the streets and living this wonderful adventure. But that paled to the joy and the feeling of a home that we had found when we peeked through those curtains into the wonderful world of the one-ring circus.»

«We learned what a well planned and well executed circus could bring to the people in it and the audience that it serves,» said Paul Binder. «Circus is something very special that needs to be nurtured and given as a gift to the audience—with a sense of joy and, dare I say, love. It always has to be present for the circus to truly touch people’s lives.»

The Project

It was the end of Paul and Michael’s European adventure. When the Nouveau Cirque de Paris’s season ended, Paul, who was becoming homesick, returned to New York City—while Michael remained in France to help the vendanges, the harvest of wine grapes, in the southwest of France. One morning, Paul woke up in his Manhattan loft with a brainstorm that he immediately shared with his cat: Why not create in New York a classical one-ring circus with the same intimacy, warmth, dedication, and artistry that he and Michael had experienced in France?

In October of 1976, Paul gathered some friends and unveiled his idea. They reacted to it more joyfully and vocally than his cat, and Paul realized that something there really touched a chord. For some time, there had been a movement toward the rebirth of classical circus in America, one that was different from both the gigantic corporate affair that was Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey and the pathetic remnants of the defunct golden era of the three-ring big top The circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) .

In New York, Hovey Burgess, who had taught juggling to Larry Pisoni (who in turn had taught Paul and Michael), had been instrumental in triggering this movement. In San Francisco, Larry Pisoni, Peggy Snider, Cecil MacKinnon, Judy Finelli, and other alumni of Burgess’s studio were already experimenting with the Pickle Family Circus. Yet even though the idea was obviously a great one, the journey was not going to be easy.

Friends came to help, some attracted by the prospect of being physically part of a circus, others by the unconventional concept of creating a resident circus in New York City. When Paul returned to Paris for the Christmas season with Fratellini, he had already set the wheels in motion. He told Michael that he was in the process of raising a quarter of a million dollars to create their own circus. «Do you want to help me?» Michael had a hard time making sense of what he had just heard but he accepted wholeheartedly.

A closet juggler, Richard Levy was an economist and teacher with a keen interest in politics and sociology. He was quick to see what a circus could bring to the life of the city, which then teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. He became the project’s champion and its chief fund-raiser. He also played the devil’s advocate, trying to bring Paul’s dream back to the real world. He nevertheless put his own house as a security for a loan—for a circus that existed only on paper.

Slifka was invited to a rehearsal at the studio that the still-to-be-incorporated New York School for Circus Arts had opened in Manhattan (of which later). Like Woodward, he went through the killer proposal, Paul’s pitch, and a slide show of the Fratellini experience. His response was: «My wife and I think it is a wonderful idea. We’d like to help.» Alan Slifka, Maggie Heimann, and William Woodward were soon lured onto the first board of directors of the newly formed, not-for-profit New York School for Circus Arts, Inc. Alan Slifka (1929-2011) would be its chairman and guiding light for the next fifteen years and would help the organization weather many financial crises. He remained its Chairman Emeritus until his death in 2011.

At first, sponsors were not easy to find. After all, the project existed mainly on paper and proposed the unfamiliar concept of a not-for-profit circus linked with a circus school. The first corporation to back the idea was New York’s giant energy provider, Con Edison: They pledged $25,000 to open the first season’s matinee shows to children from poor neighborhoods who could not afford tickets. Not only this corresponded to Paul and Michael’s sense of community service, but it also guaranteed that at least someone would see the show!

Michael and Paul also raised funds with performances in both the parks and at luxurious homes out in the Hamptons. In Washington Square Park, they renewed their friendship with Philippe Petit, who often performed there and was now world-famous and a New York icon after his stunt at the World Trade Center. Although quite an individualist, Philippe was ready to help.

Raising The Tent

Meanwhile, the school itself took shape. An artist with a fondness for the circus, Karen Gersch had learned to juggle with Hovey Burgess, practiced acrobatics and nursed clown ambitions. She fell in love with the project and put her 17th Street loft, which was always a magnet for jugglers and acrobats in need of practice space, at the disposal of the performers and would-be performers who were enrolling in the project. Karen also brought two Russian immigrants she had met recently and who she believed could help.

Nina and Gregory thought, dreamed and breathed circus. Nina was quick to see the problems with the American circus: «The three-ring circus allows only for fireworks. The beautiful, subtle art of the individual is lost.» They also needed work. When Paul described their project, Gregory expressed his opinion in typically Russian direct fashion: «You want to start a circus? You must work twenty-eight hours a day! You must steal four hours from your death!» Nina and Gregory became the New York School for Circus Arts’ first teachers.

At first, they came only four days a week to Karen’s loft. Then Nina, always the realist and uncompromising where circus arts were involved, asked, «Where is the school?» Good question. She stressed that true circus training demands seven days a week and twelve hours a day. A slightly larger space was found on Spring Street, in a storefront owned by theatre wunderkind Robert Wilson. Now, the school had a home of its own.

Students—potential performers—came. Among them were a group of kids, age fourteen to sixteen, from Charles Evans Hughes High School; they practiced tumbling at a YMCA and were brought in by their teacher. They were to become The Back Street Flyers, a staple of the Big Apple Circus’s early productions. In 1980, they would win a Silver Medal at Paris’s Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain, bringing the circus world’s attention to «the little circus that could» over there in New York.

The training of new performers and the show rehearsals took off at the Spring Street studio. Meanwhile, a tent had to be ordered. Its design followed the Nouveau Cirque de Paris’s circular, European-style big top The circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) —then practically unknown in America—but more from guess recollections than thorough technical study. It was being made in Queens and, from the start, inexperience and bad communications ran the project in trouble. Making a circus tent is not an easy matter, and more so if one doesn’t hire a professional and experienced tent maker, but budget considerations and unflappable optimism made everybody believe the home-made tent could—must—work.

Everything was now in motion for a July 4, 1977, opening. But where? The first choice had been Battery Park at Manhattan’s southern tip, but that was without reckoning on New York City’s gargantuan bureaucracy. One month before the opening, the site had moved from the green lawns of Battery Park to a barren, sand- and gravel-covered landfill on the shores of the Hudson River—which had been hopefully named Battery Park City—but there was no assurance that the endless list of authorizations and permits would be obtained in time, if ever!

July 4th came. It was a day of fireworks over Manhattan, but no Circus Day! Finally, at 5:30 am on July 9, the tent was delivered to Battery Park City. Impending despair suddenly gave way to relief, excitement, and elation. The poles had been up for a while; even the ring was in position, and the bleachers were piled up nearby. Warren Bacon, an experienced rigger who had returned from Taïwan to participate in the Big Apple Circus adventure, his team, and everyone available began the arduous process of setting up a big top The circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) for the first time.

A first setup is always a period of trials and errors, but this one was particularly frustrating. Nothing seemed to fit. It finally become apparent that something was inherently wrong with the tent. After many unsuccessful attempts, changes of technique, new measurements, brainstorms, wasted energy, and much too much sweat in the July heat, Warren came to the only conclusion: The measurements had been wrong, and the tent was too small.

Philippe Petit, who was an expert rigger, came to the rescue. He conceived a way to rig (American) The rigged apparatus used to perform an aerial act, especially a flying act. the defective tent in spite of its miscalculated size. Two weeks after its delivery, the Big Apple Circus’s green big top The circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was finally raised! Rob Libbon, who would become the circus’s first performance director, figured out how to put up the bleachers. In the meantime, on July 13, New York was victim of the worst power failure in history, leading to a total blackout. Luckily, Con Edison didn’t back out of its grant: That was about the only thing that had gone right.

«The Circus of Picture-Books and Tribal Memory»

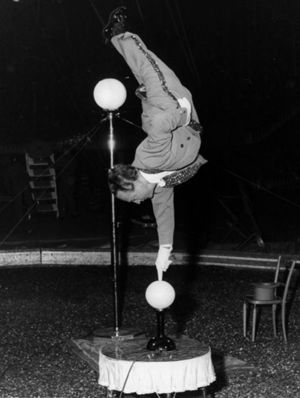

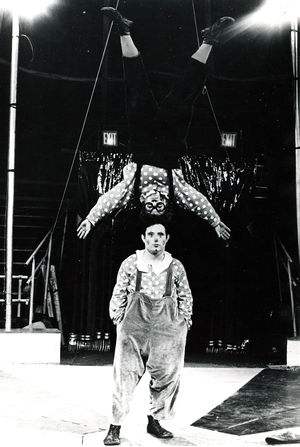

Michael Moschen, a young, very creative and elegant juggler, had joined the company in the early days of its inception. So did Paul Lubera, a flamboyant trapeze artist, and Susan Perry, an out-of-work trapeze artist, who kept a day-job as a secretary. Then of course, Paul and Michael did their juggling act, and the Back Street Flyers their tumbling act. Nina and Gregory took care of the clowning and performed a spectacular perch-pole Long perch held vertically on a performer’s shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. balancing act they had created back in Russia and which they had rehearsed during daytime at New York’s fabled nightspot, Studio 54, which provided the necessary height.

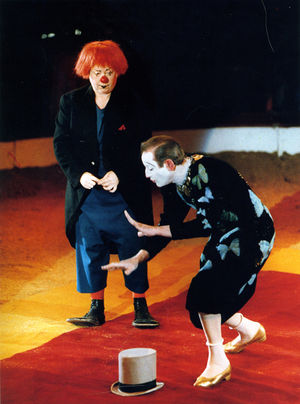

Michael also presented his parody of a trained animal act as Zakhar, the fearless trainer of Gittha, the underground (and thus invisible) soldier mole—an act whose absurd and surrealistic concept failed to be grasped by some of the show’s reviewers… In Paris, Michael and Paul had met The Indianos, a group of energetic Argentinean zapateo dancers. They had become friends, and when asked, they had agreed to come—and they did. To open the show, Nina had produced a high-spirited charivari (Italian, French) A joyous acrobatic display, mostly tumbling, originally performed by all the clowns of a circus company as a show opener. (Clowns, until the turn of the twentieth century, were generally gifted tumblers; tumbling was considered an «eccentric,» or comedic circus specialty.) with the company and the school’s students, which illustrated perfectly New York’s energy and spirit.

And the show went on! Amazingly, 45,000 people attended the Big Apple Circus during its first, ten-week season. With very little advance publicity, they found the green tent on its hot and windy stretch of landfill, paid their admission, and, most importantly, loved the show. They got it. They understood why this was not a three-ring extravaganza, and why, in many ways, this might be a better version of a circus. The press was enthusiastic; the Daily News noted, «The greatest show on earth it ain’t. (…) Just lots of funny clowns, acrobats, tumblers and trapeze artists. And something else—an intimacy with the audience that is hard to beat.»

Most importantly, the reviewers saw what the Big Apple Circus had done for the city. The New York Post declared: «For 90 minutes, New York turns into a village on fair day, binding children and adults alike in a community of sheer pleasure.» And The Village Voice: «The Big Apple Circus makes me imagine what it must have been like when a small tenting circus hit a small town—everyone in the audience knowing each other and the strange artists inspiring dinner-table talk and trips to the library and playground stunts for months afterward.» The Big Apple Circus was a success. Now, if they could only make it financially…

The following summer, the circus pitched its tent in an empty lot on Eighth Avenue—the site of the old Madison Square Garden. The organization was becoming a little more professional. Names appeared on the board of directors’ roster that would remain there for years and would be instrumental in the development of the Big Apple Circus, and Con Edison was still supporting what was now called the Ticket Fund. Nina and Gregory were still involved, although they were now teaching in their own studio.

The New York Times, which up until then had only reviewed the Ringling show when it visited Madison Square Garden, finally noticed the Big Apple Circus with an over-the-top rave: «Sometimes awkwardly, sometimes a trifle self-consciously, but altogether winningly, it is the circus of picture-books and tribal memory. A sea of children and a flooded archipelago of adults sit [around] the single ring under a green breathing canvas, as if they were the iris of an eye whose vision is focused individually and on one thing at a time.»

Yet it was not easy for «the little circus that could.» The season was too short and didn’t generate enough money to keep the organization afloat the rest of the year. In 1979, the New York School for Circus Arts introduced an arts-in-education program to provide inner-city kids with in-school circus arts training. But the Big Apple Circus didn’t perform. The choice now was either to fold the tent once and for all or pull out all the stops, find more money, and gather the right people to help fully develop both the circus and the school. The Big Apple Circus’s directors chose the latter—a heroic choice involving high risks. It was go or bust.

«The Only Circus Good Enough to Play Lincoln Center»

An executive director was hired. Judith Friedlaender was a lawyer who worked in the office of Ed Koch, the mayor of New York, and whom Paul had met and converted when trying to secure a site for the Circus. Like Maggie Heimann, Judith knew a lot of people. She was also smart, hard-working, with unbounded energy and dedication.

The Big Apple Circus gave its first performance at Lincoln Center on December 4, 1981. This was the big-time, so big-time performers were hired. The feature attractions were Philippe Petit with his beautiful highwire act, and the Flying Gaonas, the greatest flying act Any aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another. of the time, led by the charismatic triple-somersaulter Tito Gaona. The celebrated Danish equestrienne A female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Katja Schumann, heiress to the legendary Schumann circus dynasty and whom Paul had met in France, came from Europe and graced the ring with an elegant high-school A display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act on her magnificent Arabian stallion, Sky Warrior.

There were also the Bertinis, a renowned troupe of Czechoslovakian acrobats on unicycles; Carol Buckley and her baby elephant Tarra; Sacha Pavlata (also the new tent master and the school’s new head-teacher) came from Paris to perform on the cloud swing (English, American) The ancestor of the trapeze: a slack rope hanging from both ends, used as an aerial swinging apparatus. The addition of a bar in the middle led to the creation of the trapeze. . Other newcomers joined the resident company: Jim Tinsman and his beautiful wife Tisha on the Spanish web. Michael Moschen, the Back Street Flyers, and of course, Michael and Paul completed the line-up. The show was a triumph, universally praised by New York’s theater critics.

Over the years, new dedicated and powerful supporters have joined the Big Apple Circus’s board of directors, and the organization has been led by an array of talented executive directors, three of whom definitely put it on the map: Elizabeth I. McCann, one of Broadway’s finest producers; James C. McIntyre, who came from Carnegie Hall; and Gary Dunning, who hailed from the American Ballet Theater.

What really put the Big Apple Circus in a position of prominence on the international circus scene, however, was its artistic philosophy: Deep respect of the audience, priority given to the quality of the performance, constant attention to details, research of the best and most interesting acts available on the international market, and high regard for its artists. To this should be added the warmth and intimacy of its shows—as well as its many charitable activities, such as the Clown Care Unit, founded by Michael Christensen in 1986, which sent especially trained clowns to children’s hospitals all over the country.

At the time, the American circus was still attached to a three-ring culture that was not sustainable anymore, making its money out of coloring books, gadgets and food sold during the performance and paying little attention to the comforts of the spectators—who frequently sat under big tops that leaked at the first sign of rain. The Ringling shows and other enterprises that performed in arenas fared much better, although, by and large, commercialism took precedence over the show.

It introduced America to its first European circus tents, made of PVC instead of canvas, and with a metallic cupola; in time, it would also introduce the first tension tents free of quarter poles, and the first comprehensive seating system entirely boarded over the ground. It introduced theatrical lighting in the circus performance. It presented the first circus productions built around a coherent theme as soon as 1985, with original musical scores and specifically designed sets and costumes—innovations that are generally taken for granted today, but were very bold at the time.

For many years, the Big Apple Circus kept a permanent multi-national company of talented and versatile performers who provided the backbone of its themed productions and became quite familiar to a faithful audience that returned from one season to another; they provided the shows with a unique, recognizable personality. The Big Apple Circus also offered some of the brightest acts the international circus world could offer: In 1988, it brought over the Nanjing Acrobatic Troupe for a production titled The Big Apple Circus Meets the Monkey King, which mixed for the first time Chinese and Western performers; when the USSR began to crumble, the first individually contracted Russian acts to perform in the United States, The Panteleenko Brothers (in 1990) and Elena Panova (in 1991) appeared at the Big Apple Circus.

Until 1996, all Big Apple Circus productions were directed by Paul Binder, who served also as ringmaster (American, English) The name given today to the old position of Equestrian Director, and by extension, to the presenter of the show. and was the Circus’s Artistic Director. Michael Christensen, who had headed the clown department as «Mr. Stubs» until 1988, was the Creative Director. Starting in 1997, the Big Apple Circus began to invite guest directors, the first of whom was Guy Caron, the founder of Montreal’s National Circus School, and Cirque du Soleil’s first Artistic Director. Among these talented directors, the Canadian Michel Barette, Steve Smith, and Broadway director West Hyler had several return engagements.

The End of An Era

Paul Binder retired from his circus duties in December 2008, and Michael Christensen followed him the following year; both remained on the Big Apple Circus’s board of directors. The new Artistic Director—Paul’s successor—was Guillaume Dufresnoy, an insider who had joined the Big Apple Circus’s resident company in 1987 with his award-winning aerial act, Les Casaly, and graduated to Performance Director before becoming the Circus’s General Manager.

Unabated, it continued to produce quality shows. Yet, there were some changes. One of the most palpable was the loss of its resident company of performers, which impacted the family atmosphere that had become over the years a staple of the Big Apple Circus experience. Then, the board of directors, which now included several young newcomers, began to focus their rescue efforts on the charitable side of the organization, to the point where the Circus itself seemed to have become an adjunct of the Clown Care Unit and other similar programs, which were more suited to attract donors.

Important cuts in the performing unit’s support system were made, and such crucial work as marketing and press and publicity was outsourced, which didn’t help improve the situation. All this created a domino effect that steadily increased the Circus’s debt; it had reached $8,000,000 in 2016. In a desperate attempt to turn the tide, the board had hired a string of new Executive Directors who were not always much experienced in matters of showbusiness—some of whom remaining only a short time at the helm of the organization, which was certainly not an attractive position to hold; if anything, it just made matters worse.

At wits’ end, The Big Apple Circus cancelled its 2016-2017 season at Lincoln Center, and filed for bankruptcy at the end of 2016. On February 3-7, 2017, its assets, including its intellectual properties (notably its name) were sold at auction to Big Top Works, a partnership created by Compass Partners of Sarasota, Florida, for a total of $1,300,000. The not-for-profit Big Apple Circus, Ltd., New York’s One-Ring Wonder, was no more.

Epilogue?

Yet, the enterprise’s financial stability remained fragile, which led to internal feuds and reshuffling by the investors. Neil Kahanovitz, who had spearheaded the rescue of the Big Apple Circus, was pushed out and was replaced by Randy Weiner, a New York playwright, producer and theater and nightclub owner. After a failed attempt to tour small arenas in the spring/summer of 2019, the Big Apple Circus decided to limit its engagements to New York’s Lincoln Center.

The 2019 production was placed under the management of Saint Louis, Missouri’s Circus Flora team, headed by Executive Producer Jack Marsh and Cecil MacKinnon, who directed the show. Most of the old Big Apple Circus’s familiar figures had gone by then, along with a large part of its original style: It was indeed a new Big Apple Circus. Then came the coronavirus pandemic, and the Big Apple Circus didn’t appear in 2020. In July 2021, the circus was sold to a group headed by the high-wire walker Nik Wallenda, who had been featured in its 2019 production. Nick Wallenda announced the re-opening of the circus at Lincoln Center on November 11, 2021, with a show featuring. Nick Wallenda. However, the long-term future of this cherished New York institution still remains uncertain.

Источник