Is The Grand Budapest Hotel’s ‘Boy with Apple’ artwork plausible?

Boy with Apple in The Grand Budapest Hotel is a 21st-century, made-for-film creation.

Boy with Apple in The Grand Budapest Hotel is a 21st-century, made-for-film creation.

Boy with Apple is a quintessential product of the Czech mannerist, Habsburg high Renaissance, Budapest neo-humanist style. To put it another way, it is a finely constructed piece of nonsense in the same playful spirit as everything else in Wes Anderson’s delectable middle European fantasy, The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The plot of Anderson’s pink gateau of a movie, with its dowager duchesses, murderers and bakers, turns on the fate of a «priceless» Renaissance portrait of a youth pensively clawing an apple with long, bony fingers. It’s only a McGuffin in the end – it’s actually been painted for the film by artist Michael Taylor – but Boy with Apple is a fiction within a fiction that pays delicately knowing homage to the art history of old Europe. Pretending it is a real Renaissance masterpiece, what do we see?

The boy is short-haired and melancholic, his codpiece a sinister presence among the velvets and brocades in which he is clad. Unusually, he is seated, a pose normally reserved for women in Renaissance portraiture – standing would be more manly. In the shadows behind him a mysterious note is pinned behind a parted curtain. Are we to conclude that he is an unmanly young man, and if so, is the note from a male admirer?

Stylistically, the artist Johannes Van Hoytl the Younger, to whom this renowned and unimaginably expensive masterpiece is attributed, has much in common with other masters of the Renaissance in northern Europe. His fascination with the boy’s extravagantly crooked fingers resembles drawings by German artist Albrecht Dürer – in particular a self-portrait sketch in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, in which he displays almost precisely the same hand gesture. His revelation of an enigmatic message behind a curtain is reminiscent of similarly portentous objects in such Renaissance masterpieces as Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of the merchant Georg Giese surrounded with the stuff of trade, or the emblems of greed and vanity with which Quentin Metsys accuses the couple in his picture The Moneylender and His Wife. The moral emblem at the heart of Van Hoytl the Younger’s painting is of course the oldest of all Judaeo-Christian symbolic objects: the apple with which the serpent tempted Eve.

Portrait of a Young Man Artist by Bronzino (probably 1550-5). Photograph: The National Gallery, London

So this portrait is a study in temptation, and as such it is inflected with a sensuality typical of mannerist art. In 16th-century Europe, artists bored by the classical rules of the Renaissance portrayed the human figure in a more «mannered» way, stretching out limbs and necks, distorting poses. This youth’s long fingers are typically mannerist. So much about him – his short hair, finely clad form, those hints of depravity – echoes the mannerist genius Bronzino. It’s not hard to work out how such a painting found its way into an art collection in central Europe. The eccentric Habsburg Emperor Rudolph II, who filled his palace in Prague with curiosities, lured many Dutch and Flemish mannerists to his mad court. The Habsburgs were the greatest art patrons of the Renaissance, and the heritage they left behind is rich in masterpieces of Boy with Apple‘s ilk. This is exactly the kind of painting you can expect to see in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Szépművészeti Múzeum in Budapest or the picture gallery of Prague Castle.

Boy with Apple really is priceless, as an art history in-joke. The punchline, however, comes when the film’s villain realises it is missing. In its place hangs a watercolour of lesbian lovers by real-life Austrian genius Egon Schiele. In his rage at losing a completely fictional work of 16th-century art, the character smashes this modern treasure over a chair.

Источник

The story behind The Grand Budapest Hotel’s ‘Boy with Apple’ painting

Artist Michael Taylor reveals how he created the “priceless” artwork at the centre of Wes Anderson’s film.

I n Wes Anderson’s 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel, Ralph Fiennes’ debonair, dowager-bothering concierge, M Gustave, becomes embroiled in a bitter family feud after he inherits a supposedly priceless work of art. You may have presumed that the painting in question, ‘Boy with Apple’, was a genuine relic from the Renaissance era; a lesser-known portrait by one of the Dutch Masters, perhaps. In fact, it was commissioned especially for the film, with Anderson creating a backstory plausible enough to fool many viewers.

This month The Grand Budapest Hotel is being released in the UK as part of the Criterion Collection, and to mark the occasion we reached out to British artist Michael Taylor to find out more about the making of this iconic movie prop, which t he art critic Jonathan Jones has described as: “The kind of painting you can expect to see in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Szépművészeti Múzeum in Budapest or the picture gallery of Prague Castle.”

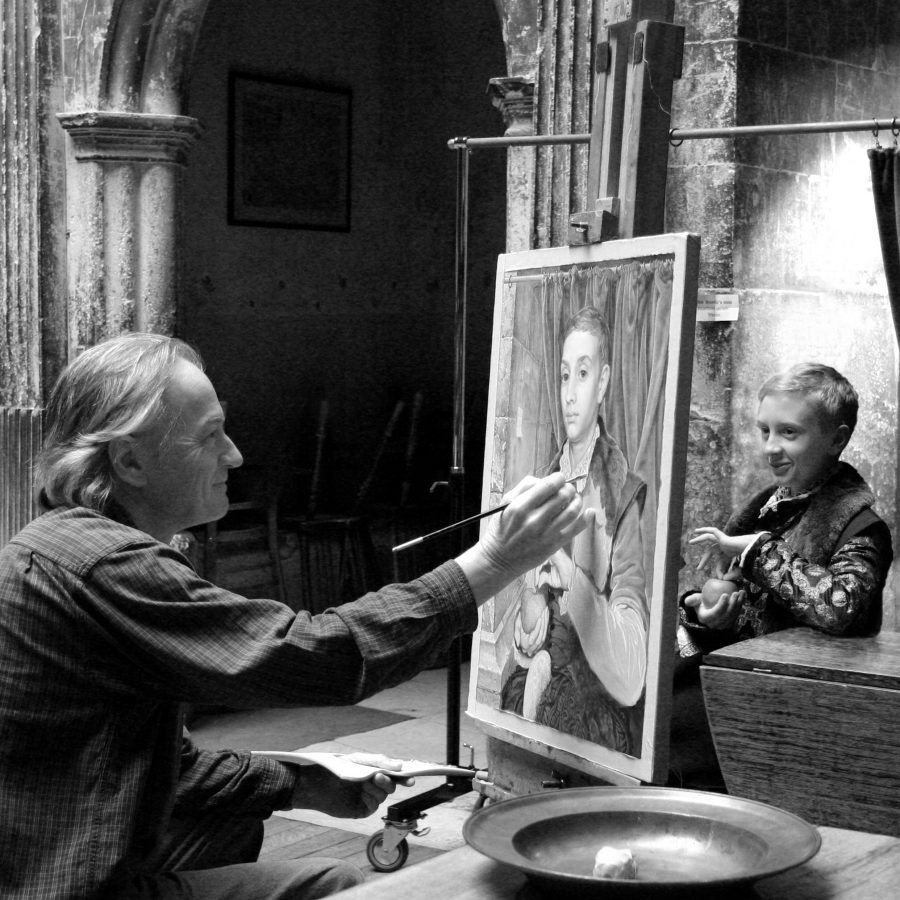

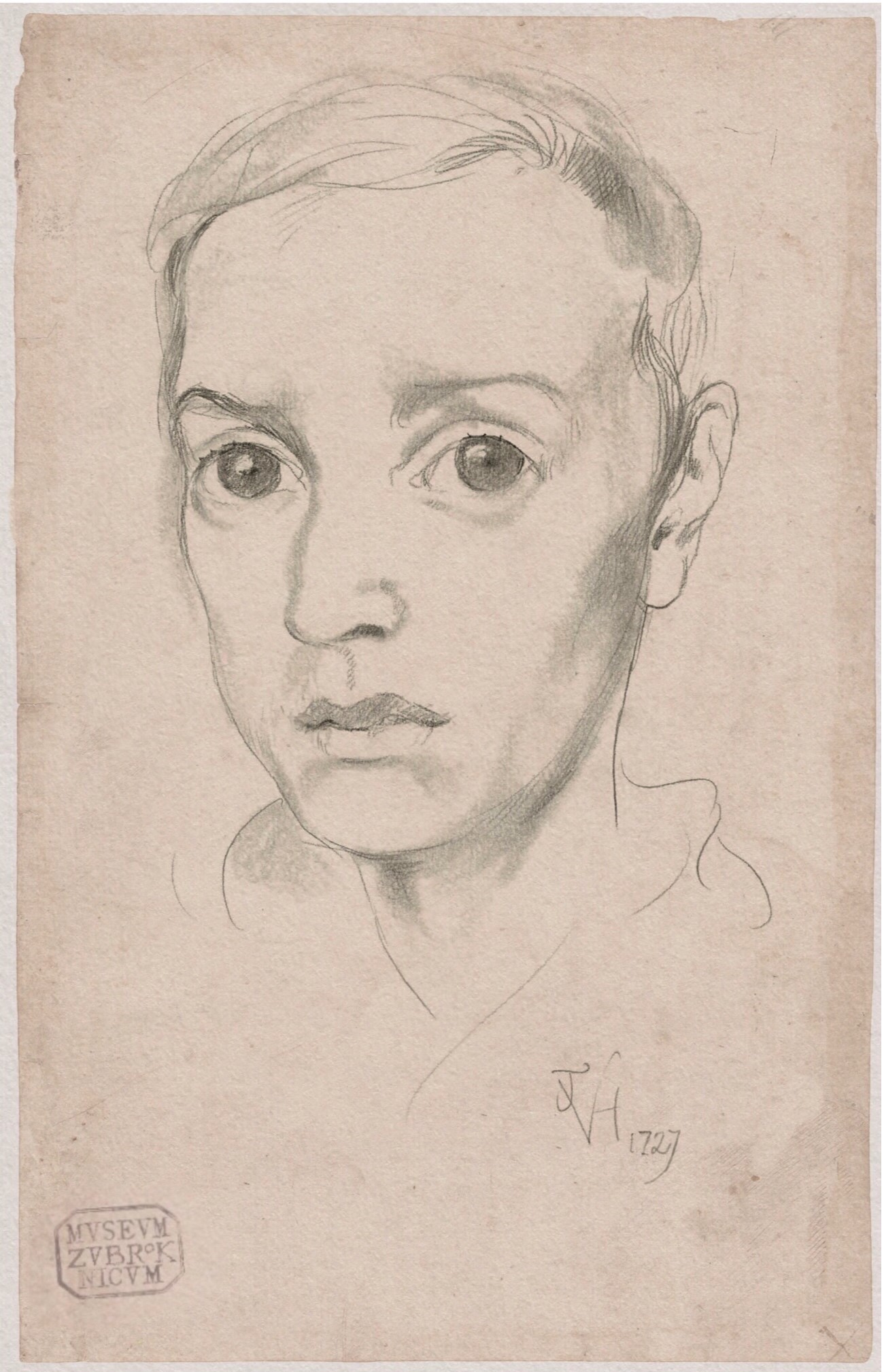

Below, Taylor provides a detailed first-hand account of how ‘Boy with Apple’ came into being, along with a selection of behind-the-scenes images and a rare, never-before-seen drawing believed to be the only authentic study for the painting still in existence.

“I was approached initially by one of the film’s producers, and shortly after Wes called me up. He gave me an outline of the plot and a rough idea of what he was looking for. I was then sent the script with my name watermarked all through it, along with a contract to sign. Quite why he settled on me I can’t say, but anyway, I got the gig.

“The brief was quite vague: something a bit Renaissance, maybe with a castle, and ‘a little bit of paper… we must have the little bit of paper.’ Oh, and it had to be funny. ‘Not very funny, just a bit funny’. As it progressed the castle went in, then got painted out, the wall was changed around a bit, a curtain rail arrived and came out again, but the hands always remained the same. There was initially a rather nice pewter plate with a bird skull, but that ended up on the painting equivalent of the cutting room floor too.

“To paint ‘Boy with Apple’, I commandeered the wonderful Jacobean Hanford House, a girl’s boarding school near my home in Dorset while the girls were away for the summer holidays. A young dancer from London, Ed Munro, was engaged to sit, and after a rummage in the film studio’s dressing-up box a costume was settled on. This evolved somewhat over time, with the red velvet sleeves borrowed from a different outfit in the end. Ed would stay with us during sittings, and I built a little set for him in one corner of the Harry Potter-like dining hall, which lent the project a nice Renaissance baronial ambience.

“Wes emailed me an assortment of reference pictures: 16th century mannerist portraits by Bronzino, some German Northern Renaissance works, photos of castles, cakes, postcards of hotels and so forth. It was all very eclectic. I had always been fascinated by the hand in that portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées in the Louvre, so for my part I knew right from the start that I wanted the hands holding the apple as they are.

“In the 16th and 17th centuries it was a gesture quite often used in paintings, and although it probably didn’t look funny to people then, I think it does to us now. It gives the boy a faintly ridiculous pomposity. The splendidly named Johannes Van Hoytl suggested to me Northern rather than Italian Renaissance, so I took it away from Bronzino and more towards Holbein or Cranach. It was pointed out to me later that there is in fact a drawing by Durer using just just such a hand gesture.

“The painting took about three months to complete, on and off. I had never attempted anything like it before, or been involved with films in any way, so I had to learn on the job; much to Wes’ understandable anxiety, particularly as filming approached and there was no painting. When I finally let him see it there were several aspects that had rather drifted away from the script which he wanted altered. Although not my usual practice to change paintings to order, I had to concede that this was after all his invention and his film, so asking for some more time I was able to make the changes he asked for.

“The drifting off began shortly after I got the script when we had some people coming to stay. I’d hidden the script somewhere for safety, but unknown to me my wife then hid it somewhere else, so when I needed to refer to it later I couldn’t find it. I didn’t dare confess to the studio that I’d lost it, nor was I keen to mention it to my wife, so I just kind of drifted on, busking it and hoping I could remember what I was supposed to do! I think it worked out okay in the end though.

“The first time I saw the completed film, I thought it was absolutely tremendous. Funny, rather dark in places, went like a train from start to finish. And of course it looked wonderful. I felt very fortunate to have played a small part of its creation. In the film the painting is described as ‘priceless’, although as far as I am aware, it was never actually valued. I suspect it would be more than I got paid for it! Another MacGuffin, the Maltese Falcon statuette, recently sold for over two million dollars, so who knows?

“Where the painting is now, I couldn’t say. When it was finished, I sent it off to Wes in a nice padded case to protect it from the rough and tumble of life on set, and haven’t seen it since, apart from in the film. [N.B. We checked with Wes and he told us, ‘I have the picture and always will.’] I like the way that after you let them go, paintings have a life of their own out in the world, but I’ve never had one turn into a movie star before.”

The Grand Budapest Hotel is now available on Blu-ray courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

Источник

Мальчик с яблоком — Boy with Apple

| Мальчик с яблоком | |

|---|---|

| |

| Художник | Майкл Тейлор |

| Год | 2012 г. |

| Середина | Масло на холсте |

Мальчик с яблоком — это картина 21-го века британского художника Майкла Тейлора . Написанная по заказу для использования в качестве реквизита в фильме Уэса Андерсона « Гранд Будапешт» в2014 году, вымышленная предыстория, написанная для « Мальчика с Apple», сыграла главную роль в сюжете фильма.

На портрете изображен мальчик в ренессансной одежде, держащий (зажимая одной рукой и сильно сжимающий другой) зеленое яблоко. Натурщицей для портрета выступил актер Эд Манро.

История

Британский художник Майкл Тейлор написал « Мальчик с яблоком» в 2012 году для будущего фильма « Отель Гранд Будапешт» . С Тейлором связался режиссер Уэс Андерсон, который попросил создать имитацию портрета эпохи Возрождения, который бы напоминал образы из истории европейского искусства . Андерсон активно вносил свой вклад в работу; В частности, он попросил, чтобы картина была сделана по образцу работ Ганса Гольбейна Младшего и Старшего , Бронзино , Лукаса Кранаха Старшего и ряда фламандских и голландских художников.

Подобное количество деталей было уделено предыстории картины. В фильме картина приписывается вымышленному «Йоханнесу Ван Хойтлу Младшему» и описывается как произведение «чешского маньериста, габсбургского высокого ренессанса, будапештского неогуманизма». Из-за того, что картина была реквизитом для фильма , которая требовала, чтобы « Мальчика с яблоком» носил под мышкой актера, Тейлор был вынужден работать на холсте меньшего размера, чем он привык.

После выхода в свет отеля «Гранд Будапешт» картина была хорошо принята. Искусствовед Джонатан Джонс из The Guardian написал полный анализ портрета, заявив, что « Мальчик с Apple действительно бесценен, как шутка об истории искусства».

Рекомендации

Эта статья о картине XXI века — незавершенная . Вы можете помочь Википедии, расширив ее .

Источник

Мальчик с яблоком — Boy with Apple

| Мальчик с яблоком | |

|---|---|

| |

| Художник | Майкл Тейлор |

| Год | 2012 г. |

| Середина | Масло на холсте |

Мальчик с яблоком — это картина 21-го века британского художника Майкла Тейлора . Написанная по заказу для использования в качестве реквизита в фильме Уэса Андерсона « Гранд Будапешт» в2014 году, вымышленная предыстория, написанная для « Мальчика с Apple», сыграла главную роль в сюжете фильма.

На портрете изображен мальчик в ренессансной одежде, держащий (зажимая одной рукой и сильно сжимающий другой) зеленое яблоко. Натурщицей для портрета выступил актер Эд Манро.

История

Британский художник Майкл Тейлор написал « Мальчик с яблоком» в 2012 году для будущего фильма « Отель Гранд Будапешт» . С Тейлором связался режиссер Уэс Андерсон, который попросил создать имитацию портрета эпохи Возрождения, который бы напоминал образы из истории европейского искусства . Андерсон активно вносил свой вклад в работу; В частности, он попросил, чтобы картина была сделана по образцу работ Ганса Гольбейна Младшего и Старшего , Бронзино , Лукаса Кранаха Старшего и ряда фламандских и голландских художников.

Подобное количество деталей было уделено предыстории картины. В фильме картина приписывается вымышленному «Йоханнесу Ван Хойтлу Младшему» и описывается как произведение «чешского маньериста, габсбургского высокого ренессанса, будапештского неогуманизма». Из-за того, что картина была реквизитом для фильма , которая требовала, чтобы « Мальчика с яблоком» носил под мышкой актера, Тейлор был вынужден работать на холсте меньшего размера, чем он привык.

После выхода в свет отеля «Гранд Будапешт» картина была хорошо принята. Искусствовед Джонатан Джонс из The Guardian написал полный анализ портрета, заявив, что « Мальчик с Apple действительно бесценен, как шутка об истории искусства».

Рекомендации

Эта статья о картине XXI века — незавершенная . Вы можете помочь Википедии, расширив ее .

Источник