A History of Apple Computers

Easyturn / Getty Images

Before it became one of the wealthiest companies in the world, Apple Inc. was a tiny start-up in Los Altos, California. Co-founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, both college dropouts, wanted to develop the world’s first user-friendly personal computer. Their work ended up revolutionizing the computer industry and changing the face of consumer technology. Along with tech giants like Microsoft and IBM, Apple helped make computers part of everyday life, ushering in the Digital Revolution and the Information Age.

The Early Years

Apple Inc. — originally known as Apple Computers — began in 1976. Founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak worked out of Jobs’ garage at his home in Los Altos, California. On April 1, 1976, they debuted the Apple 1, a desktop computer that came as a single motherboard, pre-assembled, unlike other personal computers of that era.

The Apple II was introduced about a year later. The upgraded machine included an integrated keyboard and case, along with expansion slots for attaching floppy disk drives and other components. The Apple III was released in 1980, one year before IBM released the IBM Personal Computer. Technical failures and other problems with the machine resulted in recalls and damage to Apple’s reputation.

The first home computer with a GUI, or graphical user interface — an interface that allows users to interact with visual icons — was the Apple Lisa. The very first graphical interface was developed by the Xerox Corporation at its Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in the 1970s. Steve Jobs visited PARC in 1979 (after buying Xerox stock) and was impressed and highly influenced by the Xerox Alto, the first computer to feature a GUI. This machine, though, was quite large. Jobs adapted the technology for the Apple Lisa, a computer small enough to fit on a desktop.

The Macintosh Computer

In 1984, Apple introduced its most successful product yet — the Macintosh, a personal computer that came with a built-in screen and mouse. The machine featured a GUI, an operating system known as System 1 (the earliest version of Mac OS), and a number of software programs, including the word processor MacWrite and the graphics editor MacPaint. The New York Times said that the Macintosh was the beginning of a «revolution in personal computing.»

In 1985, Jobs was forced out of the company over disagreements with Apple’s CEO, John Scully. He went on to found NeXT Inc., a computer and software company that was later purchased by Apple in 1997.

Over the course of the 1980s, the Macintosh underwent many changes. In 1990, the company introduced three new models — the Macintosh Classic, Macintosh LC, and Macintosh IIsi — all of which were smaller and cheaper than the original computer. A year later Apple released the PowerBook, the earliest version of the company’s laptop computer.

The iMac and the iPod

In 1997, Jobs returned to Apple as the interim CEO, and a year later the company introduced a new personal computer, the iMac. The machine became iconic for its semi-transparent plastic case, which was eventually produced in a variety of colors. The iMac was a strong seller, and Apple quickly went to work developing a suite of digital tools for its users, including the music player iTunes, the video editor iMovie, and the photo editor iPhoto. These were made available as a software bundle known as iLife.

In 2001, Apple released its first version of the iPod, a portable music player that allowed users to store «1000 songs in your pocket.» Later versions included models such as the iPod Shuffle, iPod Nano, and iPod Touch. By 2015, Apple had sold 390 million units.

The iPhone

In 2007, Apple extended its reach into the consumer electronics market with the release of the iPhone, a smartphone that sold over 6 million units. Later models of the iPhone have added a multitude of features, including GPS navigation, Touch ID, and facial recognition, along with the ability to shoot photos and video. In 2017, Apple sold 223 million iPhones, making the device the top-selling tech product of the year.

Источник

Personal Computer History: 1975-1984

Daniel Knight — 2014.04.26

Personal computer history doesn’t begin with IBM or Microsoft, although Microsoft was an early participant in the fledgling PC industry.

In 1976, Apple’s two Steves (Jobs and Wozniak) designed the Apple I, Apple’s only “kit” computer (you had to add a keyboard, power supply, and enclosure to the assembled motherboard), around the 6502 processor. That was also the year that Electric Pencil, the first word processing program, and Adventure, the first text adventure for microcomputers, were released. Shugart introduced the 5.25″ floppy drive; it would become a key component in the personal computing revolution.

The young industry exploded in 1977 as Apple introduced the Apple II, a color computer with expansion slots and floppy drive support; Radio Shack rolled out the TRS-80 to its stores across the nation; Commodore tapped into the pet rock craze with its PET; Digital Research released CP/M, the 8-bit operating system that provided the template for MS-DOS; and the first ComputerLand franchise store (then Computer Shack) opened.

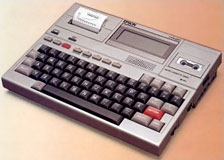

WordMaster, soon to become WordStar, was released and went on to dominate the word processing industry for years. Atari leveraged its video game experience and household name to enter the personal computing market, and Epson shipped the TX-80, the first low-cost dot matrix printer.

The third important software category, the database, blasted onto the scene in 1979 with Vulcan, the predecessor of dBase II and it’s successors. That was also the year Hayes introduced a 300 bps modem and established telecommunication as an aspect of personal computing.

1980 was the year Commodore opened the floodgates of home computing with the $299 VIC-20. Sinclair tried to one-up them with a $199 kit computer, the ZX80, which was quite popular in Britain, but it was destined to remain a bit player in the PC industry. The same can be said of Radio Shack’s fairly impressive TRS-80 Color Computer, which suffered primarily from complete incompatibility with its existing TRS-80 line.

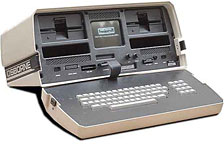

Apple III with 5 MB ProDrive hard drive.

Yet another 1980 disaster was the Apple III, which shipped with 128 KB of memory, an internal floppy drive, and Apple II emulation. Alas, it just didn’t work right, forcing Apple to recall them all, fix a number of problems, and rerelease the Apple III some time later with 192 KB of RAM. This was also Apple’s first computer to support a hard drive, the 5 MB Profile.

Estimates are that there were one million personal computers in the US in 1980.

The IBM PC

Of course, the most significant event of 1981 for the personal computing industry was the introduction of the IBM PC on August 12. This computer ran a 16-bit CPU on an 8-bit bus (the Intel 8088), had five expansion slots, included at least 16 KB of RAM, and had two full-height 5.25″ drive bays.

The second most significant event of 1981 was dependent on the first: Microsoft got IBM to agree that PC-DOS would not be an IBM exclusive. This paved the way for the clone industry, which in the end marginalized the influence of Big Blue.

Time magazine called 1982 “The Year of the Computer” as the industry grew up. By 1983, the industry estimated that 10 million PCs* were in use in the United States alone.

* Ever since IBM entered the market, the term PC has taken on a different meaning. Although it retains the original meaning of “personal computer”, the IBM architecture has so dominated the industry that it soon came to mean IBM compatible computers to the exclusion of other machines.

VisiCalc met its match in 1983 when Lotus 1-2-3 shipped for the IBM PC. That was also the year that Microsoft Word 1.0 shipped, although it remained a small player until Windows dominated the PC world.

IBM took the PC beyond the 8-bit bus when it introduced the AT (for Advanced Technology), a 6 MHz 80286-based computer with a 16-bit bus, high density 5.25″ floppies, and a new video standard, EGA.

Personal Computer History Index: 1975-84, 1985-94, 1995-2004, 2005-14, 2015-Present

Keywords: #pchistory #personalcomputinghistory

Источник

The man who made ‘the world’s first personal computer’

By Bill Wilson

Business reporter, BBC News

6 November 2015

When the definitive history of the personal computer is written, familiar and historic names such as Olivetti, Apple, IBM, will all be given recognition for their innovations of the 1960s and 1970s.

But will future generations remember visionary John Blankenbaker, and his ground-breaking invention, the Kenbak-1 Digital Computer?

It was a machine that first went on sale in 1971 and is considered to have been the world’s first «commercially available personal computer», coming on to the market some five years before Apple 1.

In fact it was a panel of experts, including Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, meeting at the Boston Computer Museum in 1987, which gave the Kenbak-1 its pre-eminent status.

Back in 1970 Mr Blankenbaker, then a computer engineer and consultant, put together his machine at his home in Brentwood, California.

«I came into a little money and decided it was time to build a small computer that could be afforded by everyone,» he tells me.

«It did not use any microprocessors, and I did the work in my garage.»

‘Affordable introduction’

In the early days of the office computer even a small device cost thousands of dollars, whereas Mr Blankenbaker’s aim was a simple computer that would cost no more than $500 (then roughly ВЈ200).

Unlike most hobby computers of the time, it was sold as an assembled and functioning machine rather than as a kit.

His ambition was that the device should be educational, give user satisfaction with simple programmes, and demonstrate as many programming concepts as possible.

«I thought of the Kenbak as an affordable introduction to the study of computer programming — I emphasized the hands on experience,» he recalls.

He demonstrated his prototype computer at a high school teacher’s convention in southern California, and when the computer went into production, its advertising was focussed on the schools market, something he now feels was a mistake.

«It should have been at the hobby-oriented people,» he says. «Schools took too long for budget approval.

«My failure was in marketing, but the machine was a success in its limited way.»

As it happens, the costs involved meant the computer had to be sold for $750 (about $4,400 in 2015) . Ironically it’s a price that would be considered an investment nowadays, when one considers that a prototype Kenbak-1 sold for $31,000 at Bonhams in New York last month.

Now one of the few remaining existing production models is expected to sell for between 20,000 ($22,000; ВЈ14,400) and 40,000 euros when it goes up for auction in Germany on Saturday, 7 November.

By the time Kenbak Corporation closed in 1973 it had completed one production run of just 50 computers, and is now virtually unknown today. Mr Blankenbaker says that as well as US sales, there were also buyers from France, Spain, Italy, Mexico, and Canada.

Pioneer days

Mr Blankenbaker, now 85, and retired to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, first became interested in computers when he was a first year physics student in the 1940s.

«When I was a freshman at Oregon State College in 1949, I read about Eniac (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer),» he says.

«This inspired me to design a computing device. It was a kludge but it inspired an interest in computers.»

Two years later he was an intern at the National Bureau of Standards where he was assigned to the Seac (Standards Eastern Automatic Computer) where he learned how a modern computer worked.

«Seac was very large; it had its own building,» he recalls. «In 1952 on graduation I worked for Hughes Aircraft Company in a department which was building a suitcase-sized computer for airborne work.»

By 1958 he had described the future principles of the Kenbak-1 machine in an article entitled «Logically Microprogrammed Computers».

Educational aim

The Kenbak-1 was designed before microprocessors were available — the logic consisted of small and medium scale integrated circuits mounted on one printed circuit board. MOS shift registers implemented the serial memory.

«[It] lacked sophisticated input-output, a large memory, and interrupts,» says Mr Blankenbaker. «Otherwise it demonstrated stored programs with three registers, five addressing modes, and a rather complete instruction set which only lacked multiplication and division.»

«The computer was intended to be educational,» he adds.

«Professionals in the field were enthusiastic but it was a struggle to convince the non-professionals that they could buy a real computer at this price.»

History of the Kenbak-1

- Designed in Los Angles in 1970 by John Blankenbaker

- First sold in 1971 for $750

- Named after Mr Blan Kenbaker

- 8-bit machine offered 256 bytes memory. Switches keyed the input and lights displayed the output

- Was capable of executing several hundred instructions per second

- Possessed a memory of about 1,000 words

- First advert in September 1971 issue of Scientific American

- Pre-dated Apple I by five years

- Maximum of 50 units produced between 1971 and 1973

- Voted «first commercially available personal computer» by Boston Computer Museum in 1987

Hidden future

The Kenbak-1’s advertising in 1971 stated: «Fun Educational Modern Electronic Technology created the Kenbak-I with a price that even private individuals and small schools can afford.

«Step-by-step you can learn to use the computer with its three programming registers, five addressing modes, and 256 bytes of memory. Very quickly you, or your family or students, can write programs for fun and interest.»

However, as Mr Blankenbaker says, he may have been more successful targeting his sales at the university students and young professionals who would go on to provide Apple’s customer base later in the decade, and indeed still do.

After the Kenbak-1 experience he worked at International Communication Sciences, at Symbolics, and at Quotron, before retiring in 1985.

He says he did not make much money out of the Kenbak-1 venture, and that one of his failings was in underestimating the development of high technology.

«In 1970, I had no vision of what the future would bring. I always felt that the current technical situation was the most that could be expected.»

Источник

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-506871794-5b6645d646e0fb002cbbdeea.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/apple-macintosh-classic-computer-118265826-5c3c0896c9e77c0001dfbfef.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/apple-s-latest-product-the-imac----51096325-5c3d4b0f46e0fb0001123369.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/first-and-third-generations-of-the-iphone-458584017-5c3d4c44c9e77c0001f2b4ff.jpg)